Hick can flourish, then, because there are fewer preconceptions about her personality. Lorena Hickok is a real person too, but the average layman is less likely to be well-versed in her story. The First Lady is famous, and therefore anything Bloom writes comes into implicit comparison with pre-existing beliefs. Admittedly, Roosevelt presents a historical challenge for her author. In a book ostensibly starring the First Lady, she remains nebulous-Bloom relies on a few overt adjectives (from the inside cover: “idealistic, patrician”) to characterize an entire protagonist. Notably, Eleanor Roosevelt is the one character who fails to brighten. I knew goddamn well I wasn’t cute.”), and on aging (“I can read for an hour or so at a time but I miss reading books by the boatload.”) Author and narrator alike do best in the Capitol-Bloom feeds off the city’s political energy. She meditates on being physically unattractive (“I wasn’t cute. Hick herself benefits the most from the setting change, however, thumping gracelessly around the White House with an amusing lack of shame. There is a gay Roosevelt cousin who adds a layer of political awareness and a secretary-mistress who complicates Franklin D. In Washington, Bloom introduces supporting characters who are interesting in their own rights. In South Dakota, Hick interacts solely with backstory-supplying villains. It’s a little too lengthy and occasionally mawkish.īut eventually, Bloom’s lyrical writing style comes into its own.

Overall, the backstory is the novel’s shakiest section. There are endless gray years in her childhood home in South Dakota. This rhetorical decision is both poignant and bleak. There is little plot to distract from the character development: It’s a close reading of a human being. At its core, “White Houses” is about a lost woman finding herself-and the story is strongest when Bloom lets it remain exactly that.Įspecially in the novel’s early chapters, Bloom sticks tightly to her narrator.

Bloom falls in love with her protagonist as much as her protagonist has fallen for the First Lady.

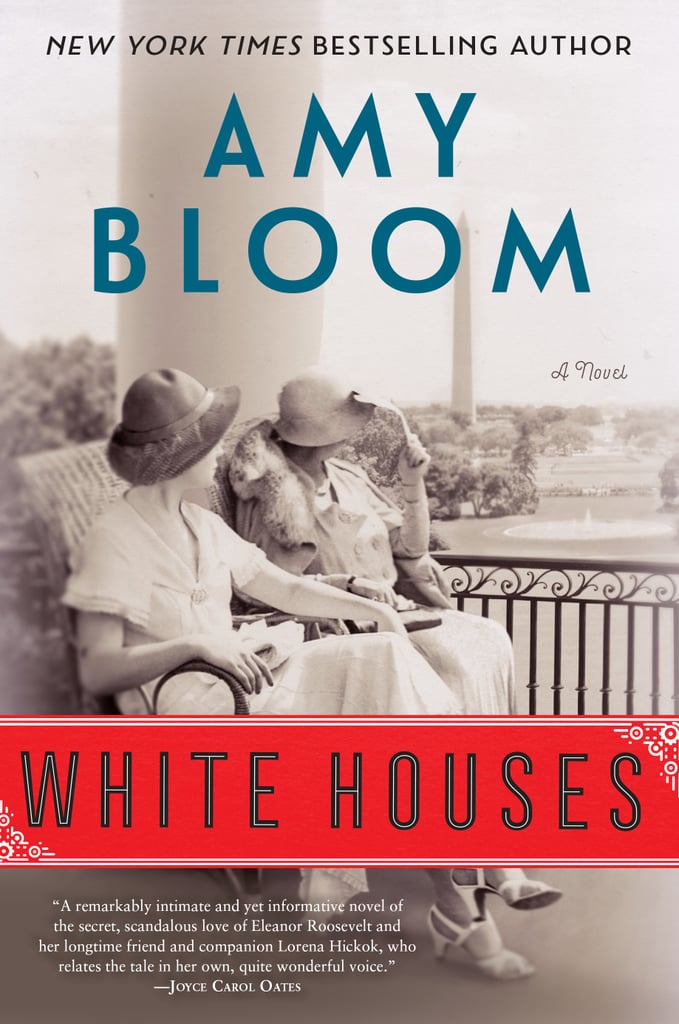

Instead, Hick (the narrator and Roosevelt’s love interest) consistently steals the show. The result, however, is far humbler-despite all appearances, this isn’t a book about Eleanor Roosevelt. The book promises gossip, drama, and maudlin affairs. It’s an intriguing concept, if primarily for a magazine tabloid. The premise of Amy Bloom’s newest novel, “White Houses,” is inherently risqué: First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt has a lesbian love affair with reporter Lorena Hickok.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)